Table of Contents

- Introduction: Shaping Taste, Shaping Futures

- 1. You Are What Your Parents Eat: How Early Flavor Preferences Take Root

- 2. The Parental Palette: Shaping Taste from the Start

- 3. Breastfeeding: A Bridge to Bitter Acceptance

- 4. Toward Healthier Palates: Implications and Strategies

- 5. Shaping Taste in the Real World: Environmental Barriers and Parental Influence

- 6. Complementary Feeding: A Second Chance to Shape the Palate

- 7. Timing and Variety: Keys to Vegetable Acceptance

- 8. Cultural Norms and Market Realitiese

- 9. Social Learning at the Table: Parents as Flavor Facilitators

- 10. Barriers to Access: The Uneven Landscape of Food Availability

- 11. Final Reflections: Building Taste, One Bite at a Time

- 1. You Are What Your Parents Eat: How Early Flavor Preferences Take Root

- Take-Home Messages

- Did You Know About Folate Receptor Autoantibodies (FRAAs) and Brain Development?

- References

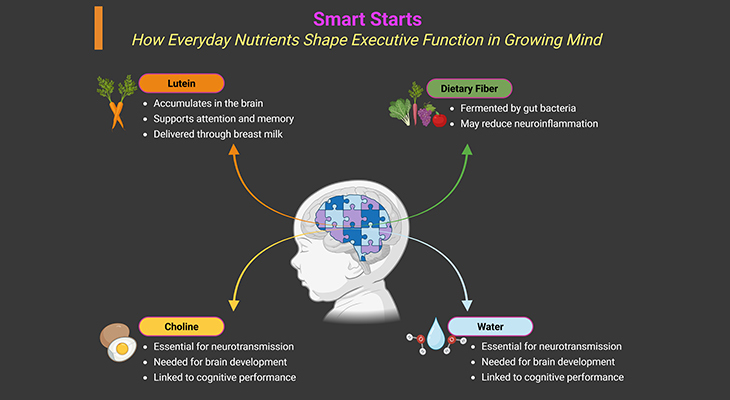

Figure 1. Taste Begins at Home: How Parents Shape Flavor from the Womb Onward. From the first swallow of amniotic fluid to the first spoonful of solids, children’s flavor preferences are shaped by what their parents eat—and how they feed. This infographic traces the critical windows of sensory development across the first 1,000 days, revealing how prenatal exposure, breastfeeding, and complementary feeding practices influence acceptance of healthful foods, especially bitter vegetables. Key insights include: (1) Prenatal flavor transmission through maternal diet; (2) Breast milk as a flavor bridge to solid food acceptance; (3) Repeated and varied exposure during complementary feeding; (4) Social modeling and feeding style as drivers of taste learning; (5) Environmental barriers that limit access to nutritious foods; (6) Relevance to neurodiverse children, including those with autism spectrum disorder. By empowering parents and addressing structural inequities, we can foster resilient palates and healthier futures—one flavor at a time.

Introduction: Shaping Taste, Shaping Futures

From the moment life begins, the human body is primed to learn—not just through sight and sound, but through flavor. The first 1,000 days—from conception to toddlerhood—represent a critical window in which taste preferences, dietary habits, and metabolic trajectories are formed. These early exposures do more than influence what children eat—they shape how they grow, how they think, and how they engage with the world.

Yet in today’s food environment, many children are drawn toward energy-dense, highly palatable foods rich in sugar, salt, and saturated fat, while rejecting vegetables, especially those with bitter profiles. This pattern is not simply behavioral—it reflects a complex interplay between biology, sensory experience, and social context. Infants are born with a heightened preference for sweetness and an innate aversion to bitterness, a trait that once protected against toxins but now poses challenges in a world where nutrient-rich vegetables are essential for long-term health.

Importantly, these preferences are not fixed. The gustatory system is plastic, especially in early life, and can be shaped through repeated exposure, positive social interactions, and parental modeling. Mothers who consume a variety of vegetables during pregnancy, lactation, and complementary feeding can influence their child’s acceptance of these foods—laying the foundation for lifelong dietary resilience.

This article explores how parental dietary habits, feeding styles, and environmental factors influence the development of flavor preferences in infancy and early childhood. We examine how prenatal flavor exposure, breastfeeding, and complementary feeding practices can promote acceptance of bitter green vegetables, and how social and economic barriers may limit access to these critical exposures.

Subtly but significantly, this discussion also holds relevance for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and related co-morbid conditions, who often experience sensory sensitivities, restricted eating patterns, and heightened food neophobia. While autism is multifactorial, emerging evidence suggests that early sensory experiences, parental modeling, and positive feeding environments may support more flexible eating behaviors—even in neurodiverse populations.

By understanding the biological roots and modifiable influences on flavor learning, we can empower families and clinicians to foster healthful eating habits from the very beginning. In doing so, we nourish not only the body, but the developing brain, the emotional landscape, and the social fabric of the child’s world.

1. You Are What Your Parents Eat: How Early Flavor Preferences Take Root

In today’s food landscape, many children consume diets that are nutrient-poor and energy-dense, falling short of recommended intake for fruits and vegetables while exceeding limits for saturated fat, sugar, and salt. In the United States, more than one in four toddlers fail to consume even a single serving of fruits or vegetables on any given day. Instead, their plates are increasingly filled with sweet snacks, salty treats, and sugar-sweetened beverages—a pattern that sets the stage for long-term health risks including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (see Figure 1) [1-6].

These dietary preferences are not simply a reflection of poor choices—they are rooted in biology. From the earliest hours of life, infants show a strong preference for sweetness, consuming more of a sweet solution than plain water and displaying facial expressions of pleasure and relaxation. This innate attraction to sugar persists through childhood and only begins to wane in adolescence. In contrast, the response to bitter tastes is markedly negative. Neonates react with gapes, nose wrinkles, and frowns when exposed to bitter solutions, and by two weeks of age, they already consume less of bitter-tasting liquids. This aversion continues throughout childhood and helps explain the widespread rejection of bitter vegetables, especially those from the Brassica genus—such as broccoli and Brussels sprouts—which are rich in polyphenols.

While these responses may seem maladaptive in a world of abundant food, they make evolutionary sense. The preference for sweetness likely evolved to guide children toward energy-rich foods during periods of rapid growth, while the avoidance of bitterness served as a protective mechanism against toxic substances. Yet, the gustatory system is not fixed—it is plastic, especially during infancy and early childhood. This means that flavor preferences can be shaped through early sensory experiences, offering a window of opportunity to guide children toward healthier choices.

2. The Parental Palette: Shaping Taste from the Start

Parents play a pivotal role in this process. Their dietary habits determine the availability and accessibility of foods in the home, and they are the primary architects of the sensory environment that shapes children’s developing palates. This influence begins not at birth, but at conception, and continues through the first 1,000 days of life—a critical window for establishing lifelong eating behaviors [1-6].

By the third trimester, the taste and olfactory systems of the fetus are functional and capable of transmitting sensory information to brain regions that regulate affective responses. During this time, the fetus swallows between 500 and 1,000 mL of amniotic fluid daily, exposing its taste buds and olfactory receptors to a dynamic flavor profile. This fluid contains compounds derived from the mother’s diet—including fruits, vegetables, spices, and even inhaled substances like cigarette smoke—which are absorbed and transmitted to the fetus.

These prenatal flavor exposures are not fleeting. Research shows they are encoded and can influence food acceptance well into childhood. For instance, children exposed to garlic in utero were more likely to consume garlic-flavored foods at ages 8 to 9 compared to those without such exposure. This suggests that flavor memory formed during gestation may have long-term effects on dietary preferences.

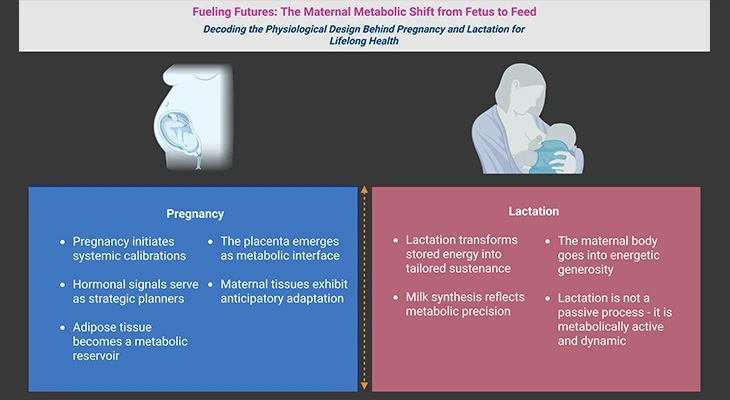

3. Breastfeeding: A Bridge to Bitter Acceptance

After birth, the flavor-shaping journey continues through breastfeeding or formula feeding. Unlike formula, breast milk reflects the mother’s dietary patterns and culinary traditions, offering infants a rich and varied sensory experience. Studies have shown that infants breastfed by mothers who consumed vegetable juices during lactation were more accepting of carrot-flavored cereal than those whose mothers avoided such juices. Notably, earlier exposure—beginning at 2 weeks postpartum—was more effective than exposure initiated at 6 or 10 weeks [1-6].

The influence of maternal diet during breastfeeding may extend well beyond infancy. In a study of 1,396 mother-child pairs, researchers found that among children breastfed for at least 4 months, each additional serving of vegetables consumed by the mother during lactation significantly increased the likelihood that the child would consume ≥1 serving of vegetables daily at age 6. These findings underscore the importance of both maternal vegetable intake and breastfeeding duration in shaping children’s long-term flavor preferences.

4. Toward Healthier Palates: Implications and Strategies

Taken together, these insights reveal that children’s flavor preferences are not solely dictated by biology—they are malleable, shaped by early exposure, parental choices, and cultural context. Factors such as socioeconomic status, food availability, and family traditions influence what parents eat and, by extension, what their children learn to accept [1-6].

Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing evidence-based strategies to promote the acceptance of bitter green vegetables and other nutrient-rich foods. By leveraging the plasticity of the gustatory system during the first 1,000 days, we can help children build healthier relationships with food—starting from the womb and extending through the dinner table.

5. Shaping Taste in the Real World: Environmental Barriers and Parental Influence

While the biological foundations of flavor preference are laid early, the environmental context in which children are raised plays a decisive role in whether those preferences evolve toward nutrient-rich foods or remain tethered to energy-dense, palatable options. One of the most critical transitions in this journey—from pregnancy to postpartum—can be accompanied by a decline in maternal dietary quality, particularly among low-income women [1-6].

Although breastfeeding mothers tend to consume more fruits and vegetables than those who formula-feed, the reality is that exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months remains uncommon in the United States. While 81% of mothers initiate breastfeeding at birth, only 20% continue exclusively by six months. These rates are even lower among African American women, with only 14% maintaining exclusive breastfeeding at six months. A major contributor to this early cessation is the return to work, often within 2–3 months postpartum, which limits opportunities for sustained breastfeeding.

Recent federal policies mandating lactation rooms in workplaces have helped extend breastfeeding duration for some women, but systemic disparities persist. Women in disadvantaged settings often face workplace barriers that restrict their ability to breastfeed consistently. As a result, many infants miss out on the flavor exposures and nutritional benefits associated with breastfeeding during this critical window.

Evidence suggests that educational interventions and social support—whether from family, healthcare providers, or employers—can improve breastfeeding rates. However, more research is needed to identify effective, scalable policies that address structural inequities and promote longer breastfeeding durations across diverse populations.

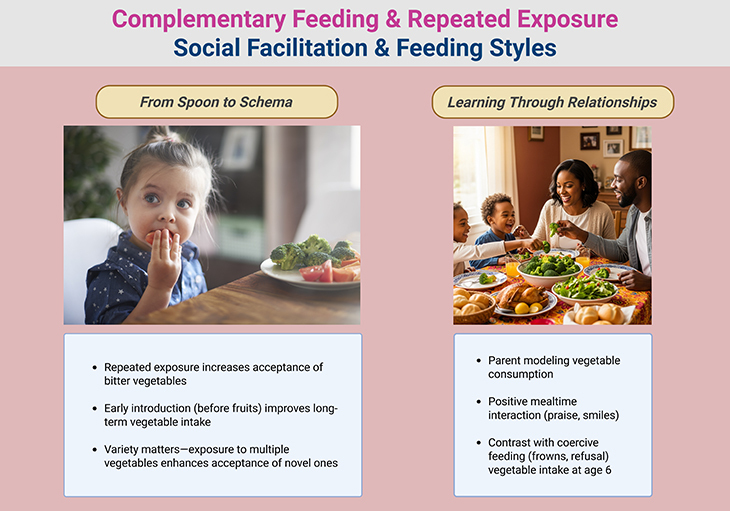

Figure 2. Complementary Feeding ~ A Second Change to Shape the Palate; and Social Learning at the Table ~ Parents as Flavor Facilitators.

6. Complementary Feeding: A Second Chance to Shape the Palate

As infants transition to solid foods around six months of age, the feeding relationship becomes increasingly interactive and bidirectional. Parents remain central figures in this process, determining what foods are offered, how they’re prepared, and how flavors are introduced. These early exposures help children build sensory schemas—mental templates for what constitutes an acceptable food in terms of taste, texture, and appearance (see Figure 2) [1-6].

Laboratory studies have identified several strategies to promote vegetable acceptance during this phase. One of the most effective is repeated exposure. Unlike sweet or salty foods, which are readily accepted on first taste, bitter vegetables often require multiple exposures before children begin to accept them. In one study, toddlers consumed more artichoke purée after just five exposures, and this acceptance persisted five weeks later.

Researchers have also explored associative learning, pairing vegetables with either calories (flavor-nutrient learning) or sweetness (flavor-flavor learning). Interestingly, these pairings were no more effective than repeated exposure alone, suggesting that familiarity may be just as powerful as conditioning in shaping taste preferences.

7. Timing and Variety: Keys to Vegetable Acceptance

The timing and variety of vegetable introduction appear to be crucial. In one study, infants who were fed vegetables exclusively during the first two weeks of complementary feeding consumed 38% more vegetables at 12 months than those initially exposed to fruits. This suggests that early exposure to vegetables—before sweeter foods dominate—may enhance long-term acceptance [1-6].

Offering a variety of vegetables also matters. In a recent trial, infants weaned between 5.5 and 6 months who were exposed to multiple vegetables (e.g., courgetti, parsnip, sweet potato) consumed significantly more of a novel vegetable (peas) than those exposed to just one type. Interestingly, infants weaned earlier (between 4 and 5 months) showed similar acceptance regardless of variety, indicating that developmental timing may influence the effectiveness of this strategy.

Together, these findings suggest that to foster vegetable acceptance, parents should offer a wide range of vegetables early and persistently reintroduce those that are initially rejected. Yet, cultural practices and commercial food environments often work against this approach.

8. Cultural Norms and Market Realities

Across cultures, the first foods offered to infants vary widely. In many European countries, vegetables are commonly introduced first—but they tend to be root vegetables like carrots and potatoes, which are naturally sweeter and less bitter. In North America and Australia, more than half of infants are introduced to infant cereals rather than vegetables [1-6].

Moreover, the commercial baby food market in the U.S. does little to promote bitter green vegetable acceptance. A recent analysis found that most single-ingredient vegetable products were red or orange vegetables, with spinach and other bitter greens appearing only in small quantities, often mixed with fruit or sweeter vegetables to mask their flavor.

These patterns reflect a missed opportunity. By prioritizing palatability over diversity, commercial offerings may inadvertently reinforce children’s innate aversion to bitterness, rather than helping them overcome it through gentle, repeated exposure.

9. Social Learning at the Table: Parents as Flavor Facilitators

As infants transition from milk to solids, their openness to new foods is often striking. However, by the second year of life, many children begin to exhibit food neophobia—a reluctance to try unfamiliar foods, particularly fruits and vegetables. This developmental shift can be deeply frustrating for parents, yet it also presents a critical opportunity. The feeding environment parents create during this phase can either reinforce neophobic tendencies or gently guide children toward healthful eating habits (see Figure 2) [1-6].

One of the most effective strategies is adopting an authoritative feeding style—a balanced approach where parents take responsibility for nutritional choices while remaining responsive to the child’s cues. This style fosters a positive emotional climate around food, encouraging exploration and acceptance. In contrast, authoritarian feeding, characterized by pressure and coercion, is linked to increased food refusals and negative associations with eating.

Children are not passive recipients in this process. They learn to associate foods with the emotional tone of mealtime interactions. For example, studies show that when parents praise children for tasting vegetables in a warm, supportive setting, acceptance increases more than with repeated exposure alone. In essence, flavor learning is not just sensory—it’s social.

Parental dietary habits also play a pivotal role. When parents consume healthful foods themselves, they not only offer these foods to their children but also model their enjoyment. This modeling effect is powerful: children are more likely to try new foods and develop positive attitudes toward vegetables when they see their caregivers eating them with pleasure.

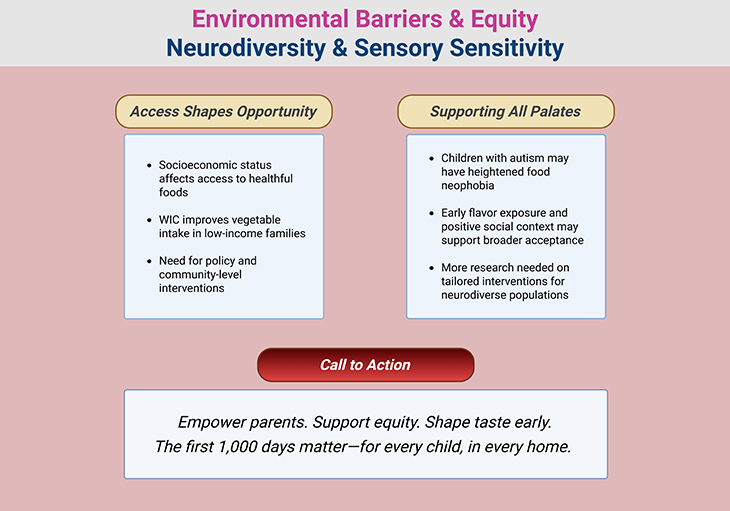

Figure 3. Barriers to Access ~ The Uneven Landscape of Food Availability; and Supporting All Palates ~ Relevance to Neurodiverse Children, Including Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD).

10. Barriers to Access: The Uneven Landscape of Food Availability

Despite the best intentions, many families face structural barriers that limit their ability to provide healthful foods. Socioeconomic status is a major determinant of dietary quality. Families in under-resourced communities may live in food deserts, where access to fresh produce is limited. Even when nutritious foods are available, they may be unaffordable, perishable, or require cooking equipment that some households lack (see Figure 3) [1-6].

Programs like the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) aim to bridge this gap by offering nutritious foods and support services to low-income families. While WIC cannot solve every challenge, participation has been shown to increase consumption of green vegetables and lentils, and reduce intake of saturated fats during the first two years of life. These outcomes highlight the potential of targeted interventions, but also underscore the need for expanded efforts—including tailored education, culturally sensitive guidance, and community-level support.

11. Final Reflections: Building Taste, One Bite at a Time

From the earliest days of life, children begin to form expectations about how food should look, taste, and smell. These preferences emerge from a complex interplay between biological predispositions, parental influence, and the broader cultural and environmental context. Mothers who consume a diverse array of vegetables during pregnancy and lactation, and who continue to offer these foods during complementary feeding, can lay the foundation for lifelong healthy eating habits.

Yet, not all parents have equal access to the resources needed to create such environments. Social, economic, and cultural factors shape the food landscape in profound ways. To promote equitable outcomes, it is essential to develop inclusive strategies that empower all families—regardless of background—to provide children with positive, repeated exposure to healthful foods in a supportive feeding environment.

In doing so, we not only nourish growing bodies—we shape the palates, preferences, and health trajectories of future generations.

Take-Home Messages

- Flavor preferences begin before birth—and they’re shaped by what mothers eat.

Exposure to flavors through amniotic fluid and breast milk lays the foundation for children’s acceptance of healthful foods, especially bitter vegetables. These early sensory experiences are biologically encoded and can influence dietary habits well into childhood. - Breastfeeding offers more than nutrition—it’s a gateway to flavor learning.

The diversity of flavors in breast milk, especially when mothers consume a variety of vegetables, promotes greater acceptance of solid foods. Longer breastfeeding duration and maternal vegetable intake are linked to higher vegetable consumption in children years later. - Complementary feeding is a critical window for shaping taste and behavior.

Introducing vegetables early, offering a variety, and using repeated exposure—even when initial rejection occurs—can significantly increase acceptance. Timing matters: early exposure leads to better outcomes than delayed introduction. - Social context matters—children learn to eat through relationships.

An authoritative feeding style, where parents model healthy eating and create a positive emotional environment, fosters openness to new foods. Coercive or authoritarian approaches may reinforce food refusal and neophobia. - Structural barriers limit access to healthful foods—and must be addressed.

Socioeconomic status, food availability, and cooking resources shape what families can offer. Programs like WIC help, but broader policy interventions and tailored education are needed to support equitable flavor learning across communities. - Flavor learning may be especially important for neurodiverse children.

Children with autism spectrum disorder often experience sensory sensitivities and restricted eating patterns. Early, gentle exposure to a variety of flavors—especially in supportive social contexts—may help broaden dietary acceptance and support nutritional resilience.

Summary and Conclusions

The development of flavor preferences in early life is a biologically driven yet environmentally modifiable process—one that begins in utero and continues through breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and early social interactions. Infants are born with an innate preference for sweetness and an aversion to bitterness, traits that once served adaptive evolutionary functions but now contribute to the widespread rejection of bitter green vegetables and other nutrient-dense foods. Fortunately, the gustatory system is plastic, especially during the first 1,000 days, allowing for meaningful intervention through early sensory exposure, parental modeling, and positive feeding environments.

Parents play a central role in shaping children’s flavor preferences—not only through the foods they offer, but through the emotional tone, feeding style, and social context they create. Authoritative feeding approaches, repeated exposure to vegetables, and modeling healthy eating behaviors have all been shown to increase acceptance of less palatable foods. Moreover, maternal consumption of vegetables during pregnancy and lactation—particularly when paired with breastfeeding—can prime infants for greater acceptance of those same flavors during complementary feeding and beyond.

However, environmental limitations such as socioeconomic disparities, food insecurity, and limited access to cooking resources continue to restrict many families’ ability to provide healthful foods. Programs like WIC offer partial solutions, but broader policy reforms, community-based interventions, and culturally tailored education are needed to ensure equitable flavor learning opportunities across populations.

Importantly, this body of research holds particular relevance for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and related co-morbid conditions, who often experience sensory sensitivities, food selectivity, and heightened neophobia. While the mechanisms linking early flavor exposure to dietary flexibility in neurodiverse populations remain underexplored, emerging evidence suggests that gentle, repeated exposure and social facilitation may support more inclusive eating behaviors.

Despite these advances, several gaps in the literature remain. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the durability of early flavor memories, the optimal timing and frequency of exposure, and the interactions between genetic predispositions and environmental inputs. Additionally, more research is required to understand how cultural norms, commercial food environments, and parental stress influence feeding practices and flavor learning outcomes. The role of paternal dietary habits, non-maternal caregivers, and digital feeding environments (e.g., screen use during meals) also warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, the first 1,000 days represent a powerful window to shape children’s flavor preferences and dietary trajectories. By empowering parents—through education, support, and structural change—we can foster a generation of children who are not only nourished, but nutritionally resilient. The path to healthier palates begins not with the child’s first bite, but with the parent’s plate.

For information on autism monitoring, screening and testing please read our blog.

References

- De Cosmi V, Scaglioni S, Agostoni C. Early Taste Experiences and Later Food Choices. Nutrients. 2017 Feb 4;9(2):107. doi: 10.3390/nu9020107. PMID: 28165384; PMCID: PMC5331538.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28165384/

(Review article exploring how prenatal exposure, breastfeeding, and complementary feeding shape long-term food preferences and obesity risk.) - Forestell CA. Flavor Perception and Preference Development in Human Infants. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70 Suppl 3:17-25. doi: 10.1159/000478759. Epub 2017 Sep 14. PMID: 28903110.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28903110/

(High-impact review detailing biological predispositions to sweet and bitter tastes, and how maternal diet influences flavor learning from gestation through weaning.) - Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Flavor perception in human infants: development and functional significance. Digestion. 2011;83 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):1-6. doi: 10.1159/000323397. Epub 2011 Mar 10. PMID: 21389721; PMCID: PMC3202923.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21389721/

(Seminal paper on sensory development, flavor transmission via amniotic fluid and breast milk, and implications for dietary programming.) - Nicklaus S. Complementary Feeding Strategies to Facilitate Acceptance of Fruits and Vegetables: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016 Nov 19;13(11):1160. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111160. PMID: 27869776; PMCID: PMC5129370.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27869776/

(This narrative review summarizes the factors that influence fruits and vegetables acceptance at the start of the complementary feeding period.) - Mennella JA, Daniels LM, Reiter AR. Learning to like vegetables during breastfeeding: a randomized clinical trial of lactating mothers and infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jul;106(1):67-76. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.143982. Epub 2017 May 17. PMID: 28515063; PMCID: PMC5486194.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28515063/

(Experimental study showing how early and varied exposure to vegetables increases acceptance and intake.) - Forestell CA. You Are What Your Parents Eat: Parental Influences on Early Flavor Preference Development. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2020;95:78-87. doi: 10.1159/000511516. Epub 2020 Nov 9. PMID: 33166966.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33166966/

(Comprehensive overview of parental dietary habits, sensory exposure, and cultural influences on flavor learning.)